Brian Roberts’ Success Comes As little Surprise To his Father

Brian Roberts’ Success Comes As little Surprise To his Father

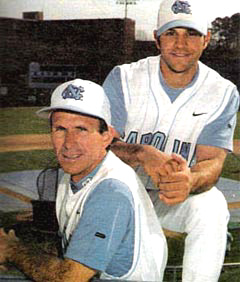

When Brian Roberts was a freshman shortstop at the University of North Carolina in 1997, he was playing a game in Chapel Hill against Seton Hall University. It was the fourth or fifth game of Roberts, first year as a college player, and Seton Hall was on what was then an annual pilgrimage south from New Jersey to play in warmer weather. And, as in most years, Seton Hall brought down a big, fire-balling pitching star to face North Carolina.

This year his name was Jason Grilli. He was 6-foot-4, and a few months later the San Francisco Giants would select him as the fourth player picked overall in the June amateur draft.

Grilli threw hard in the 90s, and his presence at Chapel Hill generated considerable interest. More than four dozen scouts were on hand to observe the big right-hander mow down opposing hitters.

Roberts, as he still is now, was dwarfed by a pitcher of Grilli’s physical stature.

He had played well in his first couple of games but basically; he was just trying to get his feet wet in college ball. He was too small to interest the scouts who had come to watch Grilli play. Roberts had no real ambition at the time other than to be a good college player.

He had played well in his first couple of games but basically; he was just trying to get his feet wet in college ball. He was too small to interest the scouts who had come to watch Grilli play. Roberts had no real ambition at the time other than to be a good college player.

Grilli, on the other hand, wanted to impress the scouts.

For Roberts’ first at-bat, the Seton Hall hurler tried to jam a belt-high fastball by him. But the little 5-foot-8 infielder was not intimidated. He swatted the Grilli pitch for a home run over the fence. When Roberts came to the plate for his second go-around against Grilli, the pitcher once gain tried to overpower him with a fastball. And Roberts once again drilled the ball over the fence.

The tiny shortstop had bested the major league prospect. Not once but twice. The scouts could not help but notice. Neither could his coach, who just happened to be Mike Roberts, Brian’s father.

“That was a breakout game for Brian,” says his father. “Brian went just there from being just a suspect with a little bit of potential to being a real prospect.”

Not enough of a prospect, however, to overcome the handicap of his size. Despite his obvious abilities, Roberts was not Jason Grilli when it came to attracting big league scouts. He hadn’t been drafted out of high school, and teams didn’t come rushing after him at UNC.

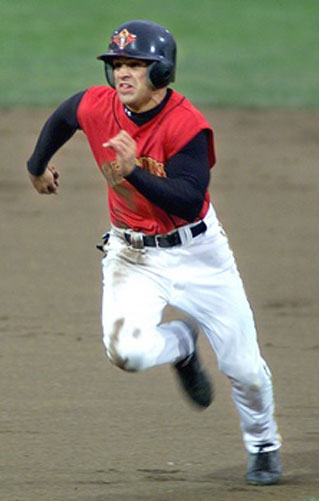

In fact, it wasn’t until after his third year as a college player, when he was named a second-team All-American and led the nation in stolen bases, that he generated enough interest to be drafted at the insistence of then-Oriole scouting director Tony Demacio.

In fact, it wasn’t until after his third year as a college player, when he was named a second-team All-American and led the nation in stolen bases, that he generated enough interest to be drafted at the insistence of then-Oriole scouting director Tony Demacio.

Demacio’s faith in Roberts certainly was justified.

While Grilli struggled through three undistinguished seasons in the majors and now languishes in the Detroit farm system, Roberts was the starting second baseman for the American League in 2005’s All-Star game.

Immediately after the All-Star game, the diminutive Baltimore second baseman led the American League in batting average, was first in on-base percentage, second in slugging average, fifth in hits, seventh in steals, and fifth in extra-base hits. Along with Miguel Tejada, Roberts is the primary reason the Orioles led the American League East for 62 consecutive days in 2005.

Like another great Oriole of the past, Cal Ripken, Roberts grew up in a baseball environment.

When Roberts was born in 1977, his father already had begun his coaching career at the University of North Carolina. Young Brian essentially was raised on the Tar Heels’ baseball field, which was just five miles from the family home. His father had been a catcher in the Kansas City organization before he turned to college coaching. And his grandfather had been associated as a quasi-executive with a Tennessee team in the Appalachian League for about a dozen years. The grandfather also coached the father on a boys’ team in Kingsport, Tennessee, just as Mike Roberts would coach his son, Brian, at UNC.

At the age of two, Brian Roberts developed a fascination for catchers’ equipment. “For some reason he loved the catchers’ gear and the catchers’ mitt,” recalls his father. “He spent a lot of time wearing the catching gear as a kid.”

It was also as a toddler that Brian Roberts began his career as a switch hitter, but with a Wiffle ball bat rather than a stick of ash or maple. “He was a natural lefty, so getting him to hit from the right side was always tough,” says Mike Roberts. “Let’s not say I made him switch hit, but I encouraged him to do it. There were times he wanted to quit switch hitting. But hopefully it’s worked out.”

The UNC coach knew his son’s size was a disadvantage when it came to baseball, so he decided to emphasize aspects of the game that could help him compensate.

“My goal,” says Mike, “was always to work on his fundamentals and make sure he had a strong and accurate arm. I didn’t know when he was a boy what size he would be, but I did know he wasn’t going to be 6-foot-2.” (The Oriole press guide lists Roberts at 5-foot-9 and 178 pounds, but that’s probably a little generous.)

So from the time when he was just a tyke, Brian Roberts and his father spent untold hours playing catch by their home. “We always worked out throwing,” says Mike, “from mail box to mail box, from mail box to sewer hole, from car to car. And I used a ball painted half black, so I could tell if he was throwing the ball with the right rotation on it. And that’s probably what I miss most today-playing catch with him. That was really a lot of fun.”

Mike Roberts lost his job at UNC after Brian’s sophomore year at the university, after a 21-year tenure at the job. The next year, Brian transferred to the University of South Carolina, from where the Orioles drafted him. His father, meanwhile, moved on to coaching baseball and serving as assistant athletic director at the University of North Carolina at Asheville and then to Florida Southern College, where he was athletic director until 2001. Today he coaches in the Cape Cod League during the summer months.

Mike Roberts felt two of his players at UNC, Walt Weiss and Chris Butera-both of whom played professional ball, Weiss in the majors – would serve as good role models for his son. They were small and were fine athletes.

“I told Brian that he wasn’t going to be the biggest guy, but that he would always throw the ball with more velocity than the other guys on the field, and if you can run faster and make contact, you can always play for a long time,” relates Mike. “I had Chris and Walt for six years. So when Brian was a kid, I thought I could teach him what they did well, because they were both good athletes and switch hitters. As a little boy, Brian’s athletic skills were similar to what I thought Chris’ and Walt’s were when they were little.”

After his first two years in high school, Brian though about giving up baseball. A lot of that probably had to do with the fact that his father was an intense coach and that Brian had been involved so deeply in baseball his entire life. He often had joined his father’s team on road trips to other colleges. He would take ground balls on the UNC infield as a kid and when the Tar Heels would take batting practice, the young Brian would be there with them, dressed in a baseball uniform. But he decided to stick with it, despite his temporary lack of motivation, and his father gives him credit for his persistence.

“The one reason I thought Brian continued to get better was because he never got to a point where he rejected practice or continued using his skills,” says Mike.

After Brian’s junior year in high school, he went away to Ohio for the summer to play baseball, a break from routine that his father thinks now was very good for him.

“He got some freedom to play with other guys,” says Mike, “and I think he got rejuvenated at that point. He played with [current Phillie] Pat Burrell. He had never played with guys nationally before. So playing with Pat and other players seemed to give him lots of new energy to continue to work.”

While Mike was the parent involved in Brian’s athletic development, his mother, Nancy, provided religious nourishment and training. Today Brian Roberts remains devoted to his Christian faith. It is as much a part of his life, perhaps, as baseball. “His mother has always been the real guiding factor in that area, more than I have,” says Mike. “I’ve tried to keep him grounded on the baseball side, and she’s really kept him grounded on the religious and Christian side.”

Mike Roberts has the reputation of being a tough coach, although he prefers not to use the word, “tough.” “Some people might use the word ‘tough,’ but I prefer to say ‘disciplined.’ I think I always asked Brian and other players to have a discipline in their work habits.”

When Brian enrolled at UNC and began playing under his father, Mike sought to be even-handed in dealing with his son.

“I didn’t think it was any different than with any other players,” he says. “I had the same rules with him that I did with anybody else. But it was probably a lot tougher on him. In any coaching situation where you’re coaching a family member, the pressure comes from more from outside sources than it comes from the family and the child. There’s just a lot more pressure from the outside.”

Mike Roberts still can sound as equitable in the way he regards Brian on the 2005 America League All-star team, he says, “I’m just happy for any young man who receives recognition for their hard work, whether it be Brian or Miguel Tejada or any of those guys.”

He also will say that he’s just as pleased to see another of his North Carolina players, the Orioles’ B.J. Surhoff, in the majors as he is his son. “It’s always special to have a former player make it to the big leagues, “ Mike Roberts explains. “I was just as happy for B.J., because B.J. is part of our family, too. But certainly, Brian making it is a thrill for my wife and I and Brian’s sister, Angie.”

It was enough of a thrill that Mike Roberts left his Cape Cod team for a game to travel to Detroit and watch his son play as an All-star.

He’s also proud, but not surprised, that his son not only is an All-star, but also has become a power hitter this season, despite his size, and is one of the Orioles’ leading home run hitters this season.

“One thing Brian, as well as other players I’ve coached, have taught me,” says Mike, “[is] don’t ever be surprised at what they might do. Look at B.J. Who ever thought he would play 19 or 20 years in the major leagues? And Rafael Palmeiro, who played against us at Mississippi State, who ever thought he might hit 600 home runs? So, no, I’m not surprised at Brian’s home runs this year. In fact, he told me, ‘Dad, the balls I hit for doubles last year have gone 10 or 15 extra feet this year.’ I guess I don’t think anyone can say they haven’t been a little bit surprised, but don’t try to limit what can do.”

And the father admits that he is proud at what his son has accomplished, just as he is proud of his daughter, an accountant in Dallas.

And he is happy nowadays to not have to worry about helping build his son’s career.

“I’m like other people now,” says Mike Roberts. “I’m no longer his coach. I’m just a fan.”